The UMKC School of Law, KC Legal Hackers and KC Digital Drive collaborated to organize and host a continuing legal education (CLE). This webinar was part of the 2020 Legal Tech Speaker Series, sponsored by Denton’s, Spencer Fane and Husch Blackwell.

The focus of the CLE was: “How technology will change the legal profession, your practice, your ethical obligations and what you can do about it.” This topic is relevant given the ongoing evolution in technology and how it is shaping all aspects of people’s lives and professions. This includes more interdisciplinary practice between lawyers and non-law professionals. People all across the country are becoming increasingly interested in the potential technology has for improving equity in the legal system and elsewhere.

The first session was entitled “Exploring Computable Contracting.” This half of the webinar was moderated by Tony Luppino, Professor of Law & Director of Entrepreneurship Programs at the UMKC School of Law. Panelists included John Cummins, Innovation Partners Ltd. and Honorary Research Fellow and University College, London; Marc Lauritsen, President of Capstone Practice Systems; and Bryan Wilson, founder of KC Legal Hackers, Editor in Chief of the MIT Computational Law Report, and a Fellow in the MIT Connection Science research group.

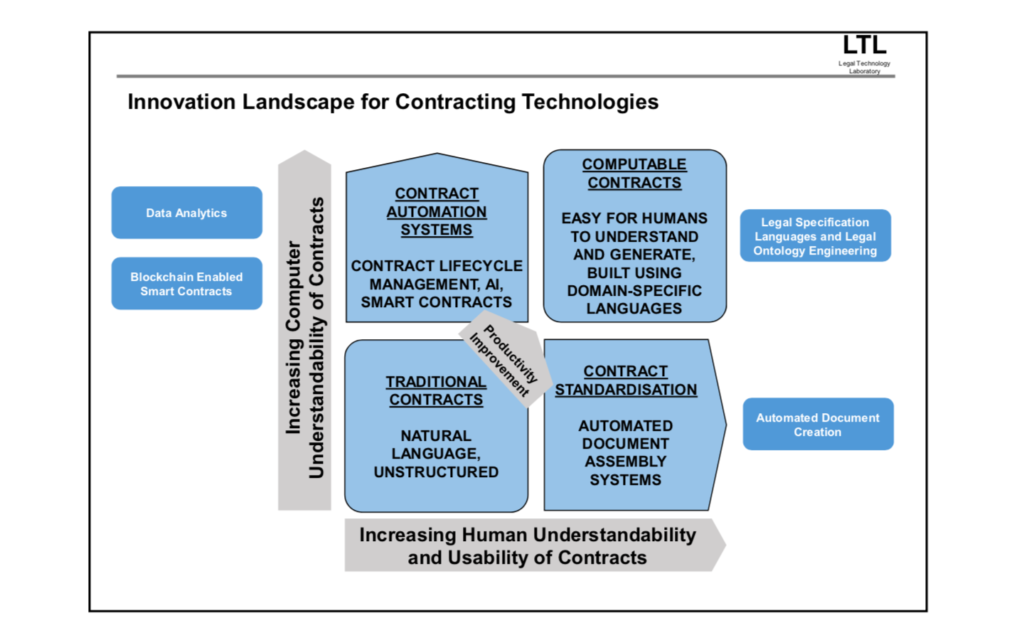

Panelists explained the many ways in which technology can be utilized in various aspects of contract law. These aspects make up the Contracts Innovation Landscape. It is important to understand the language of contracts in order to see their potential for innovation. Contracts are typically written using natural legal language. Contracts do not come from a standardized template but are drawn up for the specific needs of the parties involved. With technological tools, though, there is movement toward standardization of the information about the contract allowing for easier and more straightforward assembly.

This automation does not refer to the exact language used but the contracts’ basic structure. Metadata can be used to make contracts and the construction of contracts easier for both humans and machines through more standardized formatting.

This does not mean that human decision is removed from the process. Instead, technology allows the important decisions of what makes the most sense in each specific case to be the focus of those human decisions because the automation helps structure it. This is one example of the disconnect in communication between technology professionals, the sellers of tech products and legal practitioners. Increased knowledge and understanding between these fields will increase the potential for these kinds of innovations.

There are many of these sellers worldwide. They sell systems to help automate contracts using data from existing contracts to draft language into templates. One example is “smart contracts.” Traditionally, smart contracts have been used to describe code that performs a legal function. However, recent innovations have seen some of this code extended to include improved contracting interfaces so that it is easy for lawyers and non-lawyers alike to understand what is happening without needing to know exactly what the code itself is saying. This increases the usability of contracts and can help improve non-lawyer understanding of what it is that is being exchanged and agreed to.

There are some concerns that this kind of innovation could reduce available attorney positions. However, the panelists emphasized the importance that lawyers, clerks and other legal professionals hold in guiding and then implementing these kinds of innovations. Moreover these changes will help increase the interdisciplinarity of the legal field, which directly relates to increased access and inclusion. For example, the way contracts are re-engineered will differ for each legal specialty, and these are areas that law students could be of great use.

The second half was entitled “Ethics: Improving Access to Justice by Amending Ethical Rules.” Panelists included Stacy Butler, Professor of Practice and Director of the Innovation for Justice Program at the University of Arizona; Lucy Ricca, Fellow at the Center on the Legal Profession and Stanford Law School Special Project Advisor at IAALS; and Ellen Suni, Dean Emerita and Professor of Law at the UMKC School of Law.

This section also explored increased access, inclusivity and interdisciplinarity in the legal field. Panelists explained that there is a very high percentage of underrepresented parties in legal issues in the US, especially in areas such as evictions and family law. These underrepresented are disproportionately poor people, and their lack of counsel leads them to sign documents and take decisions without legal guidance.

Panelists explained that this lack of representation is directly linked to rules restricting law practice in this country. These rules and regulations hamper innovation due to their risk aversion. Because it is unrealistic that everyone in need of legal guidance will ever have the financial resources to access it, innovations in the ability of non-legal professionals to provide assistance and expertise are crucial to increasing equity in the US legal system.

Rules regarding fees prevent the splitting of fees between lawyers and non-lawyers. They also limit the definition of a firm and thus who can be paid for what work. Rules regarding the restructuring of legal practice prevent where, how and for whom lawyers can work. For example, a lawyer can’t practice in an organization wherein a non-lawyer is in a position of power with regard to the provision of legal services. Rules restricting advertising prevent lawyers from paying someone for recommending them, limiting the spread of helpful legal information and guidance for those in-need.

These rules are theoretically meant to protect the public in the legal world. However, this is not well-balanced with the huge need for access and justice in the US legal system. Instead, the need for public protection is overstated, and access to counsel and capital is restricted. These rules prevent non-lawyers from helping provide legal assistance at more affordable rates. They prevent meaningful collaboration between law professionals and human services professionals, which could allow a more holistic approach to legal needs. They restrict investment in legal firms from individuals other than lawyers, preventing multi-disciplinary businesses that could serve as one-stop-shops for low income clients. These restrictions fail to serve the public fully.

There are examples of efforts to change these regulations. The Utah Implementation Task Force on Regulatory Reform has created a “regulatory sandbox.” This allows non-lawyer owned entities to test out provision of nontraditional products and services to meet client needs, increasing access to assistance and thereby increasing equity and justice in the legal world. Rather than de-regulating the legal world, this re-regulates with an eye to ethics. There are requirements of risk assessments and disclosures to clients to ensure transparency, and the products provided are strenuously reviewed to ensure clients are receiving the advertised outcomes.

Although there is some pushback against these kinds of changes, younger members of the Bar and law students seem to be more open to and excited about these sorts of innovations.

This webinar was held June 15, 2020. Visit the KC Legal Hackers website and UMKC’s CLE event page to learn about future CLE opportunities. Find out more about the moderators and panelists here.